Under Virginia’s Community Policing Act, which went into effect on July 1, 2020, law enforcement officers statewide are required to collect and report demographic data about people they pull over. The data collection is intended to discourage police from engaging in racial profiling.

Earlier this month, the first nine months of data was published on an online database, allowing members of the public to review how its local law enforcement agencies conducted traffic stops over the past year.

Warrenton Police Chief Michael Kochis is fully on board with the new system. “Citizens have a right to know who their police force is stopping and why,” he said. “If we’re going to build trust with the community, we have to have transparency.”

Warrenton Police Chief Mike Kochis speaks to town council members during a March 9 work session.

The data for each locality documents the race, ethnicity, gender, and age of the driver who is stopped. Also included are the reasons for the traffic stops and whether stops resulted in warnings, citations or arrests.

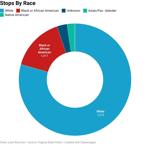

In Fauquier County, law enforcement has recorded 9,159 traffic stops between July 1, 2020, and March 31. Race data shows that white residents, who make up a large majority of the county’s population (87%), have accounted for 79% of stops. African Americans, who make up 7.8% of the population, have been involved in 15% of stops. Hispanic residents, 9.2% of the population, made up 13% of stops (since Hispanic is classified as an “ethnicity,” the data is calculated separately from a driver’s “race”).

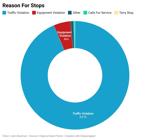

The vast majority of stops, 8,576, were initiated due to traffic violations. Equipment violations were a distant second, with 464 recorded. Also included were “terry stops”—traffic stops based on “reasonable suspicion of involvement in criminal activity.”

The numbers include stops made by the Warrenton Police Department, the Fauquier County Sheriff’s Office and Virginia State troopers operating within the county.

According to Kochis, the data “shows that officers are out there doing their job the right way: stopping people for legitimate reasons, not engaging in biases.”

But he was also quick to caution against reading too much into the data. “We have to remember that this went into effect in the middle of a global pandemic,” he said, adding that the current data doesn’t fully reflect normal policing trends.

Ellsworth Weaver

President, Fauquier NAACP

For local activists in the Black community, the data collection is seen as an important step toward greater police accountability. “It allows the community to see the operations of the police force a lot better,” said Ellsworth Weaver, president of the NAACP Fauquier County Branch.

“It’s important for people who depend on police officers to be treated in a non-biased way and that we are not antagonized or harassed because of their position of authority.”

Data collection a challenge

Although Kochis has welcomed the greater transparency, he admitted that the data collection initially caused some difficulties.

When the law went into effect, he said, the department’s existing records management system was unable to process the extra information without an expensive update. It was also unclear how the collection would be accomplished by officers in the field.

Kochis eventually decided to have his officers document the required demographic information directly on traffic tickets. Or, if an officer chooses not to ticket a driver, on “warning tickets.” A clerk reviews the tickets and inputs the data onto a spreadsheet, which is submitted monthly to Virginia State Police.

“At first I thought it would be a heavy lift,” he said. “But now that we’ve been doing it for a year, it’s not a problem.”

But for the county sheriff’s office, which has reported almost five times as many stops, collecting and organizing the data has been more of a challenge. “It’s very labor-intensive,” said Theresa Miller, the office’s records manager, “and it’s costing us $2,300 a month just in labor.”

Deputies keep records of their individual traffic stops and Miller incorporates the deputies’ information into an office-wide database. But recording everything manually causes “a lot of human error,” she said. “We spend about two to three hours a week just fixing errors” and making sure the information is in the required format.

FCSO’s records system is outdated and would require a $25,000 software upgrade to meet the community policing requirements in a less time-consuming way, according to Miller.

Fauquier County Sheriff Robert Mosier

“I think the intentions were good,” Miller said of the mandatory data collection. “They wanted to see if there were any discrepancies … there’s just already a lot on [our deputies].”

In a statement, Sheriff Robert Mosier said: “Our agency’s policies have not changed. We continue the practice of fair and impartial law enforcement.”

For the past year, data collection has only been mandatory during traffic stops. As of July 1, though, officers must now record demographic information for all stops.

It is a time-consuming process, acknowledged Weaver. But it’s necessary “to build a better relationship between police and communities.”

“Many in [the Black] community have been shell-shocked,” he said. “When we see a blue light, we freeze.”

Kochis, who has said he wants to change the culture of policing, said, “If collecting data builds trust with people who didn’t used to trust police — it’s a good thing.”

"Stop" - Google News

July 14, 2021 at 10:29PM

https://ift.tt/3B3xWlY

Traffic stop data collection increases law enforcement transparency - Fauquier Times

"Stop" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KQiYae

https://ift.tt/2WhNuz0

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Traffic stop data collection increases law enforcement transparency - Fauquier Times"

Post a Comment