Sometimes Godot shows up.

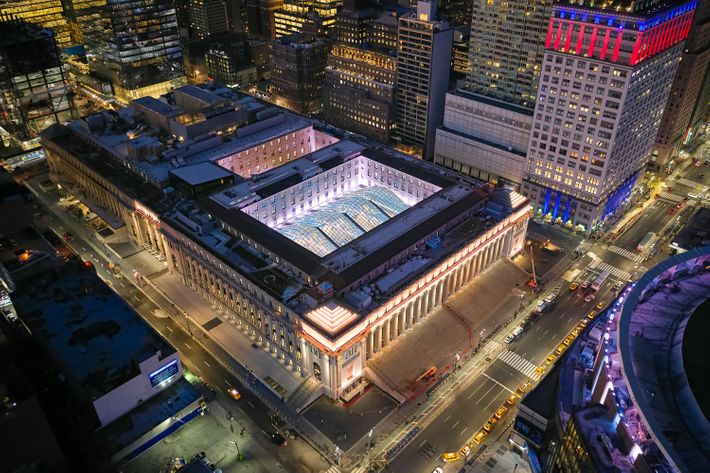

We’ve been talking about Moynihan Station for so long — 27 years, to be exact — that setting foot on the new train hall’s freshly laid Tennessee marble floors seems like one more hallucinatory experience at the end of an implausible year. Look up and you’re staring at daylight, which wavers and bends on its way through the ceiling’s glass vaults. Squint at one of the dozens of digital screens where departure times appear with icy clarity, and you half expect a boarding call for the Polar Express rather than, say, Ronkonkoma. Moynihan Train Hall is real, all right, though it’s not actually a station — more of a grand waiting room for Amtrak and the Long Island Railroad dropped into the center of the doughnutlike Farley Post Office Building. Its primary purpose is to improve upon the experience of leaving or entering Manhattan through Penn Station, a bar so low it’s buried in the basement. On that score, the $1.6 billion building succeeds. More ambitiously, the new room aims to evoke, maybe even revive, the romance of travel by rail. And yet this long-delayed mash-up of spectacle and missed opportunity doesn’t make the heart go clickety-clack.

The aspiration to lift spirits as well as move bodies matches McKim, Mead & White’s 1914 granite temple, with its Corinthian columns and imperial stairs. (It’s also well-timed, since Amtrak’s customer-in-chief will shortly chug into the White House, a marketing boost any company would die for.) A century ago, Beaux Arts architects ennobled all sorts of prosaic activities, like collecting taxes, borrowing books, sending postcards, and, yes, commuting. Now, the architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill has done the same by disemboweling the Farley building and turning its core into a skylit court. The floor of the mail-sorting hall is gone, and so are the surveillance chambers suspended overhead, where security men kept watch to make sure no checks or packages disappeared. Instead, the great trusses spanning that enormous cavity have been stripped to naked steel and repurposed to support a set of parabolic skylights. SOM has focused all the drama and expectation on that steel-and-glass latticework. All is daylight, air, and space, in a room nearly the size of the main concourse at Grand Central Terminal.

This lissome modern version of the classic steel-and-glass train sheds of Europe has plenty of recent peers: Frank Gehry’s fishlike vault over the DZ Bank in Berlin, an assortment of Norman Foster’s transparent domes (chiefly the Great Court of the British Museum and the Reichstag in Berlin), and, closer to home, that other commuter station: Calatrava’s World Trade Center Transit Hub. Mostly, though, there’s a lot of Grand Central envy going on. The interior boasts acres of expensive stone, much of it quarried from the same swath of Tennessee that furnished the other terminal, along with countless civic buildings. Instead of painted constellations, Moynihan displays a view of the actual celestial dome. Here, too, lovers have the option of meeting beneath an oversize dial clock, this one an echo of an Art Deco skyscraper’s crown, designed by Peter Pennoyer. And, as in the rival railroad’s palace, crowds arrive from any of the building’s four corners, passing through a low-ceilinged perimeter, into a soaring hall. The Farley building, too, had suffered from decades of neglect and needed a major preservation intervention that was at once radical and respectful. There are slabs of century-old riveted steel, welded columns, and a strong aroma of history. Windows have been restored or replaced, the façade returned to its pre-soot pallor.

But competing with one of New York’s most beloved architectural nodes is like rewriting Moby-Dick: the comparison is unlikely to be flattering. Grand Central is inviting, harmonious, soothing even in moments of frenzy. Moynihan self-consciously tries to reconcile old-timey graciousness and contemporary cool, muted stone and garish screens. Just inside the 33rd Street mid-block entrance, a stained-glass painting by Kehinde Wiley, framed as to fit in a Renaissance palazzo, glows from the ceiling. Black dancers cavort among the clouds with New York pigeons and a passing jet. The foyer spills out into a glass-vaulted passageway between the ornate 1914 original building and the plainer annex, built two decades later. From there, passengers move down an escalator and into a corridor, where an abundance of metal panels, stainless-steel handrails, glass railings, and a palette ranging from pewter to graphite gives the space a sober, gray-suited air. Only in a waiting room designed by the Rockwell Group does a splash of warmth relieve the austerity. There, sinuous walnut benches and wainscoting snake among gray columns, walls are tiled with white-on-blue architectural drawings of trusses and arcades, and a set of photo illustrations by the artist Stan Douglas re-create incidents from Penn Station history in epic style.

I’m a sucker for these throwbacks. I grew up loving European train stations, with their extensive menus of foreign cities and intimations of midnight border crossings, the thrilling sense of a vast polyglot land mass laced together by steel rails. Even now, those great gares and Banhöfe conjure visions of adventure: rushing to the station and grabbing a ticket to wherever the next train is headed; pulling away, while someone you love waves from the platform; meeting a passenger as she disembarks in a cloud of steam, one sleek leg at a time. These threadbare movie devices still capture the imagination because there is something enduringly romantic about the idea of being pulled across the landscape at high speed in the company of strangers, watching other lives flit by on either side of the tracks. Trains are earthbound yet temporarily isolated from the world around them.

The post-1963 Penn Station doused those fantasies. Its dank catacombs made a train seem like an unpleasant, possibly fatal thing to catch. A new train hall cannot change the complex’s basic structure. Trains still pull into and depart from their subterranean lair, connected with the land of the living by a set of narrow, marble-clad passages traversed by escalator. Moynihan was possible because the LIRR and Amtrak (but not NJ Transit) platforms that lie beneath Penn Station stretch west, past Eighth Avenue, so it made sense to bring passengers directly upstairs from various points along their length, instead of having them walk to one end of the train. The new spaces’ orderly design and abundant signage will relieve some of the feedlot feel that builds up in Penn Station at rush hour. (Remember rush hour?) No more clustering below the big board and then frantically searching for the right door when the platform is posted. But also: no waving as a train picks up speed, no platform greetings, no impromptu jumping aboard.

For all its backward glances, the Moynihan extension’s benefits are mostly tied to the future.

As an antidote to the blight that is Penn Station, the new train hall helps knit together Midtown South with the business district expanding out from Hudson Yards. Look left before entering the from West 33rd Street, and you’re looking at the Empire State Building; look right and you see the almost-1,000-foot glossy glass spike of 1 Manhattan West, also designed by SOM, at the corner of Ninth Avenue, home of the law firm Skadden, Arps. Suddenly, this once peripheral stretch of a lifeless block sits in the middle of everything. That’s one reason that, though the machinery of travel sits below ground, the building’s economic gearworks are above, in the 730,000 square feet of new Facebook offices that sprawl throughout both the original Farley building and the annex.

Given how long this project has taken to complete, and at what cost, it seems high-handed to call this a good first step, but that’s exactly what it is. Transit advocates have been frantically pointing out that the train hall’s impact on how quickly passengers can get from, say, midtown to Boston, or Battery Park to Hauppauge, is precisely nil. No train operations were improved in the making of this station, no platforms added or speeds increased. Passengers connecting from the 1-2-3 subway lines still have just as far to drag their luggage to their seats. Benjamin Kabak, a passionate analyst of New York’s transit system, groused this week that the new hall amounted to “lipstick on a pig.” But it’s more than that.

For decades, Penn Station has been the visible symbol of official disdain for public transit and intercity rail travel, and the people who depend on them. It’s been a perpetual stopgap, a signal that there was no point in getting too comfortable because, really, how long are we going to keep shuttling in and out of a 21st-century city aboard 19th-century technology? Funding is politics, politics is theater, and theater requires a fitted-out stage; New York finally — or once again — has a camera-ready set that proclaims the city’s long-term faith in rail. The power of a monument is not just cosmetic; opening Moynihan makes it possible to start closing off sections of Penn Station piece by piece in order to civilize it, rebuild it, maybe even expand it into a future Penn South, with new tracks borne into Manhattan through an as-yet-to-be-bored tunnel under the Hudson. My still nonexistent grandchildren might even live to see it all done.

"start" - Google News

December 31, 2020 at 12:30AM

https://ift.tt/38UF0o2

Penn Station’s New Train Hall Is Only a Start. But at Least We’re Starting. - Curbed

"start" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2yVRai7

https://ift.tt/2WhNuz0

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Penn Station’s New Train Hall Is Only a Start. But at Least We’re Starting. - Curbed"

Post a Comment