Efforts to end the spread of HIV in the US are slowly recovering after the Covid-19 pandemic hindered a federal initiative to end the epidemic by 2030, public health officials and researchers said.

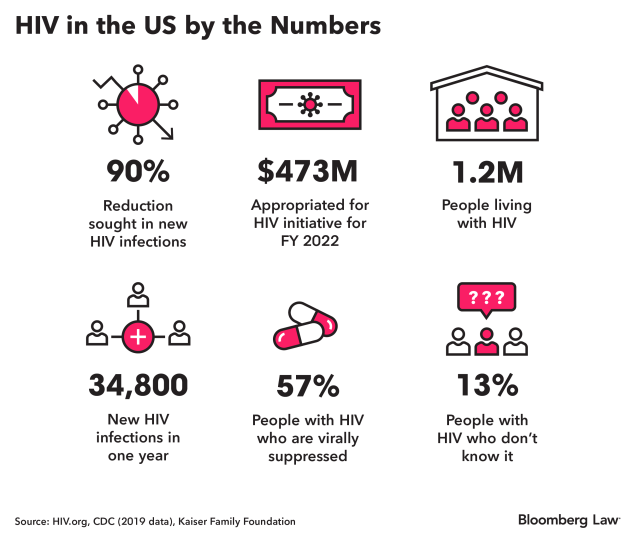

The Health and Human Services Department launched the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US (EHE) initiative in 2019 to reduce new HIV infections by 90% over the next decade. The efforts were spurred by the Trump administration and supported by the Biden administration when it took office.

The early years of this initiative have been marred by an increase in disparities, a lack of adequate funding, a workforce redirected to the pandemic, and failure to get prevention medication to Americans who need it. But the Covid-19 pandemic has also led to lessons learned for this infectious disease, with increased use of at-home testing and greater telehealth uptake.

“It is an ambitious initiative, and an ambitious initiative is what the US needed and continues to need,” said Amy Killelea, owner of public health firm Killelea Consulting. “For many, many reasons, we as a country have not found our stride just yet in really making headway to meet those ambitious goals.”

About 34,800 new HIV infections occurred in the US in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 1.2 million people had HIV, about 0.36% of the population.

The department’s efforts to end the HIV epidemic include providing more accessible and routine testing, connecting people more quickly to care when they are diagnosed, improving access to HIV prevention drugs, and directing additional funding to geographic hotspots.

‘Looking at a Reset’

Advocates working on the ground say that HIV efforts were severely affected by the pandemic and that the focus is on rebuilding.

“We are almost looking at a reset,” said Dazon Dixon Diallo, founder and president of Atlanta-based SisterLove Inc., a HIV services and advocacy nonprofit. “There’s some pretty heavy lifts that are in front of us just to even get back to the levels of progress where we were before the pandemic.”

The Biden administration said meeting these goals is still a top priority. “We’re going to do everything we possibly can to meet the goals of the EHE despite the challenge of Covid,” HHS Assistant Secretary for Health Rachel Levine said in an interview.

Levine, who did her pediatric residency at Mount Sinai hospital in the mid-1980s, saw the early years of the epidemic, where every patient with HIV she treated died. “I was there at the beginning. And I want to be there at the end,” Levine said.

Racial Disparities

One major challenge to accomplishing these goals are the racial inequities that exist within the US for HIV care.

African Americans made up 44% of new HIV diagnoses in 2019 and Hispanic Americans about 30%, both disproportionately higher than their total representation in the US population, according to the CDC.

“What we’re seeing with the confluence of HIV, Covid-19, now monkeypox, is the same communities are being impacted over and over,” said Naina Khanna, co-executive director of the Positive Women’s Network—USA, an advocacy organization for women living with HIV.

Dixon Diallo said her organization has been seeing more people further along in their HIV/AIDS progression when they’re diagnosed than typically seen, especially young Black men who have sex with men.

“If we don’t center blackness in this response and recognize the racial inequities in how HIV is being responded to in the United States, we will not get to the end of HIV,” she said.

Khanna said the way to prevent disparate impacts on communities of color is to not just focus on the biomedical solutions like drugs, but to ensure that people with HIV have access to health care, stable housing, food, and quality of life. The new National HIV/AIDS Strategy adds quality of life as a measure for success.

Increasing Funding

The top priority for advocates and the administration is to get Congress to increase funding for the initiative.

When the Trump administration set out to accomplish this, the HHS estimated what it would take to do so, and Congress has yet to meet that funding. Over the first three years of the initiative, the HHS requested a total of $1.677 billion. Congress appropriated $1.144 billion. For fiscal 2023, the HHS requested $850 million, and the House draft appropriations bill would allocate just under half of that, $422 million.

Levine said that is her main priority in the coming months. “The budget resources for the first three years didn’t get us where we want to go, so we’re going to need funding, but I am very hopeful.”

It’s not just about increased funding, but also “flexibility in the funding,” said Houston Department of Health Assistant Director Marlene McNeese, who is also the co-chair of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS. Disease funding is often done specific for each condition, but it’s most effective where there is “a blending and offering of services.”

Allowing funding for HIV, sexually transmitted infections, drug use, and general public health efforts to be used in conjunction could maximize its impact, she said.

“We can’t afford to isolate HIV as the only infectious disease that is disproportionately impacting Black and brown people, for example. We have to look at it as a whole bundle,” Dixon Diallo said.

Key Tools

The Biden administration plans to reinvest in efforts to get people who are at risk of contracting HIV on a prevention medication, known as pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP.

The Trump administration launched a program in late 2019 with the drug’s manufacturer, Gilead Sciences Inc., to give the drug away for free to 10,000 Americans each year over the next decade, but it was largely unsuccessful. As of July 2022, the program has 5,200 active enrollments and 500 conditionally enrolled participants, Kaye Hayes, HHS deputy assistant secretary for health-infectious diseases, said.

“We have failed when it comes to PrEP access in this country,” Killelea said. An estimated 1.1 million people could benefit from being on PrEP, but only about 25% are getting it.

The free PrEP program was launched when there were only two branded drugs for PrEP, but now there are 11 manufacturers marketing generic drugs, Killelea said. As a result, the drugs will be cheaper and easier to obtain.

Getting people on PrEP and keeping them on the medication is also about access to lab testing and support services, Killelea said, and in that regard, the Covid-19 pandemic has taught health-care providers a lot.

“We’ve seen a huge uptick in HIV self-testing,” Killelea said. “We saw an acceleration of the need to meet people where they were, especially at a time where they could not come into brick-and-mortar clinics.”

The pandemic led to a massive increase in the use of at-home tests for the Covid-19, and HIV is “poised for a revolution” on that front, said Jeffrey Crowley, former director of the Office of National AIDS Policy under President Barack Obama.

The monitoring standards for people on PrEP can be a burden, but allowing people to collect their own specimen at home can increase testing adherence, Crowley said. As insurers have been forced to pay for home testing during Covid-19, this could push them to do the same for self-sample collection for PrEP testing.

Workforce Challenges

The reallocation of HIV staff to the Covid-19 pandemic response has been a “huge and significant challenge,” Killelea said.

Most of those individuals, who were intended to run efforts to end the epidemic, haven’t returned to their prior work. Many are also retiring or moving out of the public health workforce, leaving HIV efforts in a lurch at a critical time.

The Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS is looking at the “ways in which we can strengthen the HIV workforce capacity to make up for some of those losses,” McNeese said.

Advocates for ending HIV say even if the initiative’s ambitious goals aren’t met—including efforts to reduce new infections by 90% by 2030—any moving of the needle is positive.

“It was always a stretch goal, and Covid set us back and the funding set us back,” said Crowley, program director of the National HIV/AIDS Initiative at Georgetown University Law Center. He expects that the US will fall short of its end goal, but will still produce major results. “I don’t think we think of that as failure.”

"Stop" - Google News

August 19, 2022 at 04:57PM

https://ift.tt/A8ISx5R

Initiative to Stop HIV's Spread Gains Post-Pandemic 'Reset' - Bloomberg Law

"Stop" - Google News

https://ift.tt/vMX76wk

https://ift.tt/lWvDeJP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Initiative to Stop HIV's Spread Gains Post-Pandemic 'Reset' - Bloomberg Law"

Post a Comment